Learn by example: Making it easier to understand GStreamer

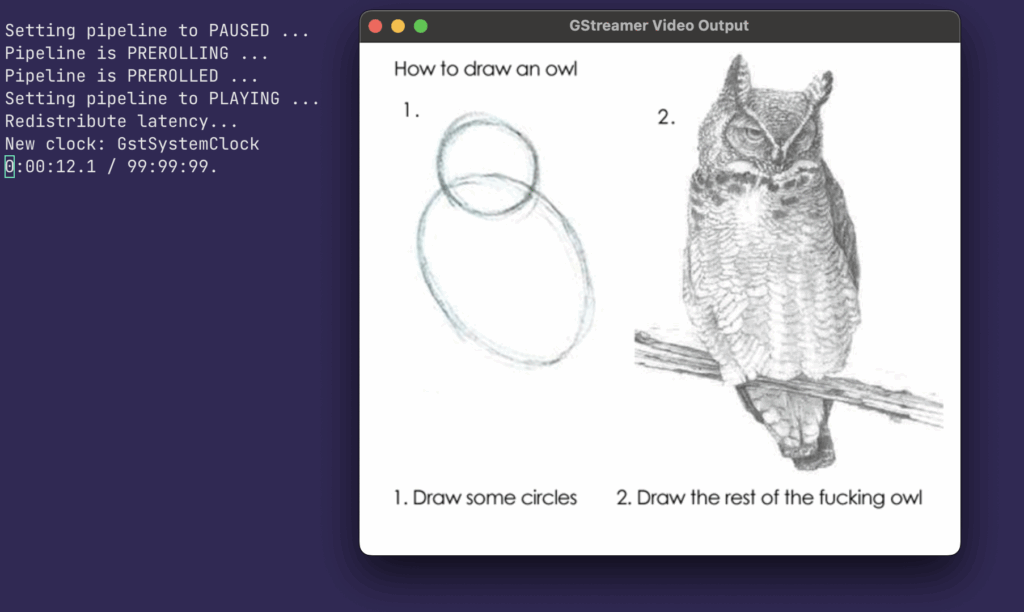

We like step-by-step learning.

We like step-by-step learning.

I have been using and learning GStreamer multimedia framework for the last +5 years, during this time I have also sent back some contributions. My first contribution was the implementation of the Rust version of the HLS sink element in 2021 (hlssink3). But I cannot say that I had completely grasped the framework concepts, it is a very large project and full of conventions. You can only learn those conventions by reading the GStreamer code, writing GStreamer applications, and participating in the community. Still I constantly find myself thinking about pads, elements, pipeline, etc, and learning something new.

Recently, I thought about yet another way to deepen my knowledge of GStreamer: write GStreamer myself! Of course I am joking here, but why not a greatly simplified version of the framework focused on learning the basic concepts. Things like pads, elements, pipeline and buffers and some time/clock handling will get you a long way. I get asked frequently about "how to learn GStreamer" and my answer is always: write code with GStreamer. Today, we will write "GStreamer code" from scratch, so you won't feel overwhelmed by all the information. We will call it "GStreamer Mini" (or gst_mini) and it is written in Python.

The Core Concepts and Objects

GStreamer is an object oriented framework, we have classes inheritance, properties, all the usual suspects (OOP abstractions). On top of those, like all code frameworks, we have core classes that we use to build upon. We will learn about Buffers, Pads, Elements, Pipeline, Clocks.

Buffers

Buffers hold the data we want to send through the pipeline. Buffers can hold any kind of data, GStreamer does not impose any limits on that. Ideally, buffers hold data that is temporal and produced over time in a streaming way (thus the name "streamer"). You can add anything to buffers, people has been using it to hold coded multimedia data, but you can use it to hold readings from your thermostat (that could be a cool GStreamer element actually). Trimming buffers to their bare bones fields, we are left with presentation time (PTS), duration, flags, and data.

from enum import Flag, auto

from typing import Any

class BufferFlags(Flag):

"""Buffer flags similar to GstBufferFlags."""

NONE = 0

DISCONT = auto() # Discontinuity in the stream

EOS = auto() # End of stream marker

DELTA_UNIT = auto() # Indicates the buffer is not decodable by itself

class GstBuffer:

"""

Simplified GstBuffer carrying timestamped data.

Corresponds to GstBuffer in gstbuffer.h:80-133

"""

def __init__(self, pts: float, duration: float, data: Any, flags: BufferFlags = BufferFlags.NONE):

"""

Create a buffer.

Args:

pts: Presentation timestamp in seconds (like GST_BUFFER_PTS)

duration: Buffer duration in seconds (like GST_BUFFER_DURATION)

data: Payload data (dict for simulated frames, or segment info)

flags: Buffer flags (DISCONT, EOS, etc.)

"""

self.pts = pts

self.duration = duration

self.data = data

self.flags = flags

def has_flag(self, flag: BufferFlags) -> bool:

"""Check if buffer has a specific flag."""

return bool(self.flags & flag)

def set_flag(self, flag: BufferFlags):

"""Set a flag on the buffer."""

self.flags |= flag

def unset_flag(self, flag: BufferFlags):

"""Unset a flag on the buffer."""

self.flags &= ~flagWe also define here some minimal flags we can set in our buffers. GStreamer has way more flags than those for buffers, but the EOS, DELTA_UNIT, and DISCONT will get us a long way. Those flags are direct takes from the real GStreamer codebase.

Clocks

The next concept we gonna implement are Clocks. As a streaming over time framework clocks are a very important concept for timing and syncronization. GStreamer implements multiple types of clocks, the basic definition of a clock in GStreamer is that it is always increasing through time (never goes backwards) and produces an absolute time. We will use the Python's time module monotonic function and write a wrapper class around it with some helpers.

import time

from typing import Tuple

class GstClockReturn:

"""Return values from clock operations."""

OK = "ok"

EARLY = "early"

UNSCHEDULED = "unscheduled"

BADTIME = "badtime"

class GstClock:

"""

Simplified GstClock for timing and synchronization.

Corresponds to gst_clock_id_wait in gstbasesink.c:2381

"""

def __init__(self):

"""Create a clock."""

self._start_time = None

def start(self):

"""Start the clock (called when pipeline goes to PLAYING)."""

self._start_time = time.monotonic()

def get_time(self) -> float:

"""

Get current clock time in seconds.

Returns:

Time in seconds since clock started, or 0 if not started

"""

if self._start_time is None:

return 0.0

return time.monotonic() - self._start_time

def wait_until(self, target_time: float) -> Tuple[str, float]:

"""

Wait until the clock reaches the target time.

This is similar to gst_clock_id_wait in gstbasesink.c:2381

Args:

target_time: Target time to wait for (in seconds)

Returns:

Tuple of (GstClockReturn, jitter in seconds)

- jitter > 0: woke up late

- jitter < 0: woke up early

- jitter = 0: perfect timing

"""

if self._start_time is None:

return (GstClockReturn.BADTIME, 0.0)

current = self.get_time()

wait_duration = target_time - current

if wait_duration <= 0:

# Already past target time - return immediately with negative jitter

jitter = -wait_duration

return (GstClockReturn.OK, jitter)

# Sleep until target time

time.sleep(wait_duration)

# Calculate jitter (how far off we were)

actual_time = self.get_time()

jitter = actual_time - target_time

return (GstClockReturn.OK, jitter)

The Clock class will help us to track progress of time after a start instant. It also has a wait_until method which will be essential later for us to handle synchronisation in our elements. Again, those methods have direct relation to real GStreamer methods.

Elements

Elements are the steps of a GStreamer pipeline. Elements may produce, process, and receive buffers over time. Elements are specialised and focused on one function they process the buffers. I have talked about the different types of elements in GStreamer in my previous blog post "A brief introduction to GStreamer". Here we will represent the most basic functionality of elements in GStreamer plus some helper methods.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from enum import Enum, auto

from typing import Optional

from .pad import GstPad

from .segment import GstSegment

class GstState(Enum):

"""Element states (simplified version of GstState)."""

NULL = auto()

READY = auto()

PAUSED = auto()

PLAYING = auto()

class GstElement(ABC):

"""

Base class for all pipeline elements.

Elements are the processing units in a pipeline.

"""

def __init__(self, name: str):

"""

Create an element.

Args:

name: Element name

"""

self.name = name

self.state = GstState.NULL

self.src_pad: Optional[GstPad] = None

self.sink_pad: Optional[GstPad] = None

self.segment = GstSegment()

self.pipeline: Optional['GstElement'] = None # Will be set by pipeline

def log(self, message: str):

"""

Log a message with element context.

Args:

message: Message to log

"""

print(f"[{self.pipeline.clock.get_time():.3f}s] {self.name}: {message}")

def create_src_pad(self, name: str = "src") -> GstPad:

"""

Create a source pad.

Args:

name: Pad name

Returns:

Created source pad

"""

self.src_pad = GstPad(name, self)

return self.src_pad

def create_sink_pad(self, name: str = "sink") -> GstPad:

"""

Create a sink pad with chain function.

Args:

name: Pad name

Returns:

Created sink pad

"""

self.sink_pad = GstPad(name, self)

return self.sink_pad

def link(self, downstream: 'GstElement'):

"""

Link this element to a downstream element.

Args:

downstream: Element to link to

"""

if self.src_pad is None:

raise ValueError(f"{self.name} has no source pad")

if downstream.sink_pad is None:

raise ValueError(f"{downstream.name} has no sink pad")

self.src_pad.link(downstream.sink_pad)

def set_state(self, state: GstState):

"""

Change element state.

Args:

state: New state

"""

if self.state == state:

return

old_state = self.state

# Handle direct jumps (e.g., NULL -> PLAYING)

# Go through intermediate states

if old_state == GstState.NULL and state == GstState.PLAYING:

self.set_state(GstState.READY)

self.set_state(GstState.PAUSED)

self.set_state(GstState.PLAYING)

return

elif old_state == GstState.NULL and state == GstState.PAUSED:

self.set_state(GstState.READY)

self.set_state(GstState.PAUSED)

return

self.state = state

# Call subclass handlers

if state == GstState.READY and old_state == GstState.NULL:

self.on_ready()

elif state == GstState.PAUSED and old_state == GstState.READY:

self.on_paused()

elif state == GstState.PLAYING and old_state == GstState.PAUSED:

self.on_playing()

elif state == GstState.PAUSED and old_state == GstState.PLAYING:

self.on_paused_from_playing()

elif state == GstState.NULL:

self.on_null()

# State change hooks (can be overridden by subclasses)

def on_ready(self):

"""Called when transitioning to READY state."""

pass

def on_paused(self):

"""Called when transitioning to PAUSED state."""

pass

def on_playing(self):

"""Called when transitioning to PLAYING state."""

pass

def on_paused_from_playing(self):

"""Called when transitioning from PLAYING to PAUSED."""

pass

def on_null(self):

"""Called when transitioning to NULL state."""

passI tried to keep this as simple as possible. One important part of this code is the handling of transition of states of elements.

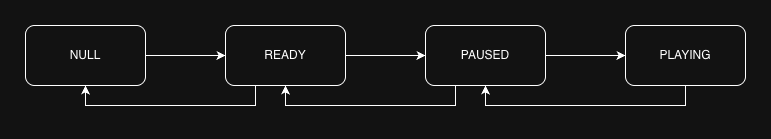

Elements always transition between states in order: NULL → READY → PAUSED → PLAYING. This is critical and allows elements to configure themselves for pre-processing or reset their internal state. Never skip states!

Elements always transition between all the following states in order:

- NULL : Initial state of elements or you can think of it as an uninitialized state;

- READY : Preparation of the element;

- PAUSED : This is when the element is basically ready to start processing data;

- PLAYING : Indicates the element is ready or already processing data.

You can read in much more detail about each of those states in the official documentation.

Lastly, we add a few methods to help us create pads on our elements. Pads are the next concept we will dive into.

Pads

This might be a new concept for you, but you can think of pads like pipes where you push buffers between elements. You need to connect pads from a source element to a destination or sink element. Pads are another critical concept in GStreamer. Elements may contain one or many pads which can be dynamically created or static to the element (always present).

Our Pad implementation in gst_mini is greatly simplified. But I have tried to keep it relatable to the actual Pad implementation in the GStreamer codebase. Pads have a peer pad, which is populated when the pad is "connected". A pad connection is a complex process in GStreamer, but the essence is that pads need to be compatible to connect. Pads have a "type", which is called "caps" or capabilities, defining what type of data the pad is capable of handling. We are not representing capabilities in our codebase. We will be responsible and only connect compatible pads in our examples, promise.

import threading

from typing import Callable, Optional, TYPE_CHECKING

from enum import Enum, auto

from .buffer import GstBuffer

if TYPE_CHECKING:

from .element import GstElement

class GstFlowReturn(Enum):

"""Return values for pad operations (similar to GstFlowReturn)."""

OK = auto()

EOS = auto()

FLUSHING = auto()

ERROR = auto()

class GstPad:

"""

Simplified GstPad for connecting elements.

Corresponds to gst_pad_push / gst_pad_chain_data_unchecked in gstpad.c:4497-4586

"""

def __init__(self, name: str, element: 'GstElement'):

"""

Create a pad.

Args:

name: Pad name (e.g., "src", "sink")

element: Parent element

"""

self.name = name

self.element = element

self.peer: Optional['GstPad'] = None

self.chain_function: Optional[Callable[[GstBuffer], GstFlowReturn]] = None

# Thread safety - similar to GST_PAD_STREAM_LOCK

self._lock = threading.Lock()

self._flushing = False

def link(self, peer_pad: 'GstPad'):

"""

Link this pad to a peer pad.

Args:

peer_pad: The pad to link to

"""

self.peer = peer_pad

peer_pad.peer = self

def set_chain_function(self, func: Callable[[GstBuffer], GstFlowReturn]):

"""

Set the chain function for this pad.

Args:

func: Function to call when receiving buffers

"""

self.chain_function = func

def push(self, buffer: GstBuffer) -> GstFlowReturn:

"""

Push a buffer to the peer pad.

This is similar to gst_pad_push() in gstpad.c:4795

Args:

buffer: Buffer to push

Returns:

GstFlowReturn indicating success/failure

"""

if self.peer is None:

return GstFlowReturn.ERROR

# Call peer's chain function - this is the synchronous call

# that makes chain calls blocking (gstpad.c:4560)

return self.peer._chain(buffer)

def _chain(self, buffer: GstBuffer) -> GstFlowReturn:

"""

Internal chain function handler.

Similar to gst_pad_chain_data_unchecked in gstpad.c:4497

Args:

buffer: Buffer received

Returns:

GstFlowReturn from the chain function

"""

# Acquire stream lock (GST_PAD_STREAM_LOCK at gstpad.c:4509)

with self._lock:

if self._flushing:

return GstFlowReturn.FLUSHING

if self.chain_function is None:

return GstFlowReturn.ERROR

# Call the element's chain function (gstpad.c:4560)

return self.chain_function(buffer)

One aspect of Pads that we must learn is the "chain function". The chain function of a pad is the main way the buffer is handled by the pad and consequently by the element that the pad belongs to. When a source element pushes buffers to its src pad, the sink chain function of the peer pad is called. We implement this in our code and it is similar to what the GStreamer codebase does as well.

The call stack of the chain function would look like something like this:

datasource - PUSHING buffer 0

encoder.chain() - RECEIVED buffer

encoder.chain() - PUSHING encoded buffer downstream

segmenter.chain() - RECEIVED buffer

segmenter.chain() - PUSHING segmented buffer downstream

publisher.chain() - RECEIVED buffer

publisher.chain() - RETURNING OK to caller

segmenter.chain() - RETURNING OK to caller

encoder.chain() - RETURNING OK to caller

datasource - PUSH RETURNED: OKWe will dive more on this process in the future.

Pipeline

Another central concept of GStreamer are pipelines. As you might have guessed, pipelines hold a collection of elements that must work in synchrony. Pipelines trigger operations on elements and hold the shared concept of time among its elements. Elements must be added to a pipeline to work properly in GStreamer. In most cases, your GStreamer based application will be built around a pipeline. Pipelines can be hold very complex graphs with many elements.

import time

from typing import List

from .element import GstElement, GstState

from .clock import GstClock

class GstPipeline:

"""

Pipeline manages a collection of linked elements.

Similar to GstPipeline in GStreamer.

"""

def __init__(self, name: str):

"""

Create a pipeline.

Args:

name: Pipeline name

"""

self.name = name

self.elements: List[GstElement] = []

self.clock = GstClock()

self.base_time = 0.0

self.state = GstState.NULL

def add(self, *elements: GstElement):

"""

Add elements to the pipeline.

Args:

*elements: Elements to add

"""

for element in elements:

self.elements.append(element)

element.pipeline = self

def link(self, src: GstElement, dst: GstElement):

"""

Link two elements together.

Args:

src: Source element

dst: Destination element

"""

src.link(dst)

def set_state(self, state: GstState):

"""

Set the state of all elements in the pipeline.

Args:

state: Target state

"""

print(f"[{self.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pipeline: Setting state to {state.name}")

# Special handling for PLAYING state

if state == GstState.PLAYING and self.state != GstState.PLAYING:

# Start the clock

if self.clock._start_time is None:

self.clock.start()

# Set base_time (corresponds to base_time in gstbasesink.c:2350)

# In a real pipeline, this synchronizes multiple sinks

self.base_time = self.clock.get_time()

print(f"[{self.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pipeline: base_time set to {self.base_time:.3f}s")

self.state = state

# Propagate state change to all elements

for element in self.elements:

element.set_state(state)

def run(self, duration: float = 30.0):

"""

Run the pipeline for a specified duration.

Args:

duration: How long to run in seconds (default: 30s)

"""

print(f"[{self.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pipeline: Running for {duration}s...")

try:

# Set to PLAYING if not already

if self.state != GstState.PLAYING:

self.set_state(GstState.PLAYING)

# Run for specified duration

start = time.monotonic()

while time.monotonic() - start < duration:

time.sleep(0.1)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print(f"\n[{self.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pipeline: Interrupted by user")

finally:

# Clean shutdown

print(f"[{self.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pipeline: Stopping...")

self.set_state(GstState.NULL)Our simplified pipeline provides two main functionalities. It allows us to add elements and to change the state of the pipeline which is then reflected to all its elements in order. The pipeline also hold the clock which is shared among all elements of that pipeline, this is essential to provide synchronous execution. When a pipeline starts the time is captured, and that becomes the base time of all processing.

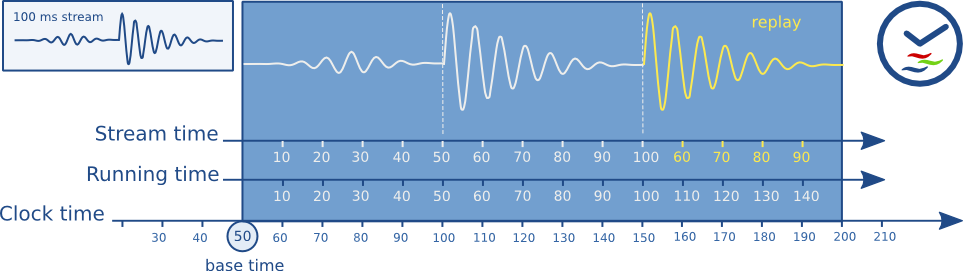

Segment

The last core concept we will represent is the concept of a GstSegment. Understand segments is important to decipher the time synchronisation in GStreamer. Segments allows us to convert the PTS of a buffer to its processing time based on the rate we want to process data. No matter if a pipeline process live content or pre-recorded content we want the processing to happen based on time. The realtime rate makes sense when processing live content or playing back the content, but if we are processing pre-recorded information we may want to process all the data of a 2 hours movie in an instant. GstSegment is an event in GStreamer, but we won't be talking about events in gst_mini for now. We introduce the concept of segment here to keep our code minimally relatable to the GStreamer codebase.

class GstSegment:

"""

Simplified GstSegment for stream time to running time conversion.

Corresponds to gst_segment_to_running_time in gstsegment.c:822-867

"""

def __init__(self, start: float = 0.0, stop: float = None, rate: float = 1.0, base: float = 0.0):

"""

Create a segment.

Args:

start: Start time of the segment (in stream time)

stop: Stop time of the segment (None = no limit)

rate: Playback rate (1.0 = normal speed)

base: Accumulated running time from previous segments

"""

self.start = start

self.stop = stop

self.rate = rate

self.base = base

def to_running_time(self, position: float) -> float:

"""

Convert stream time position to running time.

Formula from gstsegment.c:822:

running_time = (position - start) / rate + base

Args:

position: Position in stream time (e.g., buffer PTS)

Returns:

Running time, or -1 if position is outside segment boundaries

"""

# Check if position is within segment boundaries

if position < self.start:

return -1.0

if self.stop is not None and position > self.stop:

return -1.0

# Convert: (position - start) / rate + base

running_time = (position - self.start) / self.rate + self.base

return running_timeThe following formula is how we transform the buffer time in the relative running time of the pipeline:

$$ running_time = \frac{position - start}{rate} + base $$

The $position$ (or PTS) of the buffer is relative to the $start$ of the pipeline. Then this difference needs to be adjusted by the $rate$ of playback (which may be 1 in live or realtime pipelines). The $base$ is the base time of the segment, which can be 0 or more. A pipeline might produce many segments, which have a monotonically increasing base time which is the end of the previous segment.

Why it is important to learn how to convert the buffer PTS to the running time? Because you will, at some point, find yourself in need to synchronise your element processing of a buffer to the global clock.

Creating Elements in gst_mini

We have a bare bones GStreamer mini implementation, but how to create elements? In this section we will create a few elements and connect them together to see processing happening using our gst_mini framework implementation.

The first element we will create is a "fake sink" element. This element does nothing, it just receive buffers and log information about those buffers.

from ..core.element import GstElement

from ..core.pad import GstFlowReturn

from ..core.buffer import GstBuffer, BufferFlags

class FakeSink(GstElement):

def __init__(self, name, sync: bool = False):

super().__init__(name)

# properties

self.sync = sync

# state

self.buffer_count = 0

self.sink_pad = self.create_sink_pad("sink")

self.sink_pad.set_chain_function(self._chain)

def on_ready(self):

self.buffer_count = 0

def _chain(self, buffer: GstBuffer) -> GstFlowReturn:

if buffer.has_flag(BufferFlags.EOS):

self.log("Received EOS")

return GstFlowReturn.EOS

# Extract timestamp

pts = buffer.pts

# Convert stream time to running time (gst_segment_to_running_time)

# Corresponds to gstbasesink.c:2207

running_time = self.segment.to_running_time(pts)

if running_time < 0:

self.log("Buffer outside segment, dropping")

return GstFlowReturn.OK

# Synchronization (gst_base_sink_do_sync)

if self.sync and self.state.name == 'PLAYING':

# Calculate clock time: running_time + base_time

# Corresponds to gstbasesink.c:2356

clock_time = running_time + self.pipeline.base_time

# Wait on clock (gst_base_sink_wait_clock at gstbasesink.c:2381)

self.log(f"Waiting for clock_time={clock_time:.3f}s...")

_, jitter = self.pipeline.clock.wait_until(clock_time)

jitter_ms = jitter * 1000

if jitter >= 0:

self.log(f"Clock wait complete (jitter: {jitter_ms:+.1f}ms)")

else:

self.log(f"Buffer late (jitter: {jitter_ms:+.1f}ms)")

self.buffer_count += 1

self.log(f"Processed {repr(buffer)}")

return GstFlowReturn.OKWe implement the basic functionality of a sink element, but without any other logic. The most interesting part of this code is that we implement the clock synchronisation similar to what the real GStreamer code does. We use the segment to calculate the running time and then use the pipeline clock to wait for that butter PTS in the pipeline clock before proceeding with processing. This is how sink elements, like displays can show the video frames at the exact time they need to be displayed to users.

We can now start creating a pipeline and using our new fakesink. This is already a good example of how the concepts and classes we introduced previously work together.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Simple example showing buffer synchronization.

Manually creates buffers and pushes them through a sink,

demonstrating the clock wait mechanism.

Pipeline:

Manual buffers → FakeSink (with sync)

"""

from gst_mini import GstPipeline, GstState, GstBuffer, GstSegment, FakeSink

def main():

print("=" * 80)

print("Simple Synchronization Example")

print("=" * 80)

print()

print("Manually pushing 5 buffers with increasing timestamps")

print("Watch for clock waits demonstrating synchronization")

print()

print("=" * 80)

print()

# Create pipeline

pipeline = GstPipeline("simple-pipeline")

# Create sink

sink = FakeSink('fakesink', sync=True)

# Add to pipeline

pipeline.add(sink)

# Set up segment

sink.segment = GstSegment(start=0.0, rate=1.0, base=0.0)

# Set to PLAYING

pipeline.set_state(GstState.PLAYING)

print(f"[{pipeline.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pushing buffers manually...\n")

# Create and push buffers with increasing timestamps

for i in range(5):

pts = i * 2.0 # 2 seconds apart

buffer = GstBuffer(

pts=pts,

duration=2.0,

data={'segment_num': i, 'buffers': range(60), 'duration': 2.0}

)

print(f"[{pipeline.clock.get_time():.3f}s] Pushing buffer {i} with PTS={pts}s")

sink.sink_pad._chain(buffer)

print()

# Cleanup

pipeline.set_state(GstState.NULL)

print()

print("=" * 80)

print("Notice:")

print(" • Each buffer waited until its timestamp matched clock time")

print(" • running_time = PTS (since segment.start=0, segment.base=0)")

print(" • clock_time = running_time + base_time")

print(" • Synchronization formula: wait until clock >= clock_time")

print("=" * 80)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()I highly encourage you to modify this code yourself. An especially interesting part I liked to adjust was the segment $rate$, which directly represents the rate of processing or playback of the buffers we are producing (where $rate = 1.0$ is normal speed, $rate > 1.0$ is faster, and $rate < 1.0$ is slower). We have a lot of logging and you will notice the changes in the time of processing. I find it super cool to play around.

Now we can implement a camera like element, producing buffers live.

"""LiveSource - Simulates live camera generating frames."""

import threading

import time

from ..core.element import GstElement, GstState

from ..core.buffer import GstBuffer, BufferFlags

from ..core.pad import GstFlowReturn

class LiveSource(GstElement):

"""

Source element that generates frames at a fixed rate (like a camera).

Demonstrates live sources that cannot be paused - they keep generating data.

"""

def __init__(self, name: str, fps: int = 30):

"""

Create a live source.

Args:

name: Element name

fps: Frames per second to generate

"""

super().__init__(name)

self.fps = fps

self.frame_interval = 1.0 / fps # Time between frames

self.frame_count = 0

self.dropped_frames = 0

self._thread = None

self._running = False

self._start_time = None

# Create source pad

self.src_pad = self.create_src_pad("src")

def on_playing(self):

"""Start generating frames when entering PLAYING state."""

self.log(f"Starting frame generation at {self.fps} fps")

self._running = True

self._start_time = time.monotonic()

self._thread = threading.Thread(target=self._generate_frames, daemon=True)

self._thread.start()

def on_null(self):

"""Stop generating frames when entering NULL state."""

self.log("Stopping frame generation")

self.log(f"Generated {self.frame_count} frames, dropped {self.dropped_frames} frames")

self._running = False

if self._thread is not None:

self._thread.join(timeout=1.0)

def _generate_frames(self):

"""

Frame generation loop (runs in separate thread).

This simulates a live camera that captures frames at regular intervals.

"""

next_frame_time = time.monotonic()

while self._running:

current_time = time.monotonic()

# Check if it's time for the next frame

if current_time >= next_frame_time:

# Calculate PTS (presentation timestamp)

# This is the time since we started, in seconds

pts = current_time - self._start_time

duration = self.frame_interval

# Create buffer with frame data

buffer = GstBuffer(

pts=pts,

duration=duration,

data={

'frame': self.frame_count,

'timestamp': pts,

'content': f'frame_{self.frame_count:06d}'

}

)

# Try to push buffer downstream

# This call may block if downstream is slow or queue is full

result = self.src_pad.push(buffer)

if result == GstFlowReturn.OK:

if self.frame_count % self.fps == 0: # Log every second

self.log(f"Generated frame {self.frame_count}, PTS={pts:.3f}s")

self.frame_count += 1

else:

# Push failed (queue full, flushing, etc.)

self.dropped_frames += 1

if self.dropped_frames % 10 == 1:

self.log(f"Dropped frame {self.frame_count} (total dropped: {self.dropped_frames})")

# Schedule next frame

next_frame_time += self.frame_interval

else:

# Sleep until next frame time

sleep_time = next_frame_time - current_time

if sleep_time > 0:

time.sleep(min(sleep_time, 0.001)) # Sleep in small increments

# Send EOS when stopping

eos_buffer = GstBuffer(pts=0.0, duration=0.0, data={}, flags=BufferFlags.EOS)

self.src_pad.push(eos_buffer)

def get_stats(self) -> dict:

"""Get statistics about frame generation."""

return {

'frames_generated': self.frame_count,

'frames_dropped': self.dropped_frames,

'fps': self.fps,

}This is a slightly more complex element implementation, but all the complexity is just to simulate a device producing content as specific time. We still leverage all the gst_mini framework and publish buffers to pads just like in real GStreamer code.

Now we have everything necessary to create our first full gst_mini pipeline and play it out.

from gst_mini import GstPipeline, GstState, FakeSink, LiveSource

def main():

print("=" * 80)

print("Simple Synchronization Example")

print("=" * 80)

print()

print("Using LiveSource to generate buffers at 1fps")

print("Watch for clock waits demonstrating synchronization")

print()

print("=" * 80)

print()

# Create pipeline

pipeline = GstPipeline("simple-pipeline")

# Create elements

source = LiveSource('videotestsrc', fps=1)

sink = FakeSink('fakesink', sync=True)

# Add to pipeline

pipeline.add(source)

pipeline.add(sink)

# Link elements

source.link(sink)

# Set to PLAYING

pipeline.set_state(GstState.PLAYING)

# Runs for 5 seconds

pipeline.run(5)

# Cleanup

pipeline.set_state(GstState.NULL)

print()

print("=" * 80)

print(f"Completed example, total processed frames by sink: {sink.buffer_count}")

print("=" * 80)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()Look at the logs and you will notice all the processing was right on time. I have also created a few other elements we can play around.

The fun continues

We have also S3Sink, HLSSegmenter, VideoEnc, and Queue. Those extra elements can be combined to create more interesting pipelines for education. This is not dealing with real multimedia content, this is just for demostration. Still I tried to follow some of the GStreamer concepts with them and may use them in future blog posts. For now, here we can see a more complex example combining some of those extra elements:

from gst_mini import GstPipeline, GstState, LiveSource, Queue, HLSSegmenter, S3Sink

def main():

print("=" * 80)

print("Full HLS Pipeline Example")

print("=" * 80)

print()

print("Pipeline: LiveSource → Queue → HLSSegmenter → S3Sink")

print("- LiveSource generates 30 frames/sec")

print("- Queue decouples threads (max 10 buffers, leaky upstream)")

print("- HLSSegmenter creates 6-second segments")

print("- S3Sink uploads with synchronization")

print()

print("Watch for:")

print(" • Frame generation at steady rate (Thread A)")

print(" • Queue filling/emptying")

print(" • Segment creation every 6 seconds")

print(" • Clock waits before upload (Thread B)")

print(" • No blocking of frame generation!")

print()

print("=" * 80)

print()

# Create pipeline

pipeline = GstPipeline("hls-pipeline")

# Create elements

source = LiveSource("camera", fps=30)

queue = Queue("queue", max_size=10, leaky="upstream")

segmenter = HLSSegmenter("segmenter", target_duration=6.0)

sink = S3Sink("s3sink", bucket="live-streams", sync=True)

# Add to pipeline

pipeline.add(source, queue, segmenter, sink)

# Link elements

pipeline.link(source, queue)

pipeline.link(queue, segmenter)

pipeline.link(segmenter, sink)

pipeline.set_state(GstState.PLAYING)

# Run for 20 seconds

pipeline.run(duration=20.0)

pipeline.set_state(GstState.NULL)

# Print statistics

print()

print("=" * 80)

print("Statistics:")

print("-" * 80)

source_stats = source.get_stats()

print(f"LiveSource: {source_stats['frames_generated']} frames generated, "

f"{source_stats['frames_dropped']} dropped")

queue_stats = queue.get_stats()

print(f"Queue: {queue_stats['buffers_in']} in, {queue_stats['buffers_out']} out, "

f"{queue_stats['buffers_dropped']} dropped")

print(f"S3Sink: {sink.segment_count} segments uploaded")

print("=" * 80)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()I highly encourage you to study the logs and add more logs in critical parts like state changes, pad handling buffer processing. You will create a very useful mental model that will help you read real GStreamer element code and also help you create your own elements. I like to browse through the elements in the gst-plugins-rs repository a lot. I really enjoy Rust and find the Rust bindings to be really good and readable, also using Rust for writing elements will prevent some common mistakes as the Rust type system is leveraged greatly to guide you.

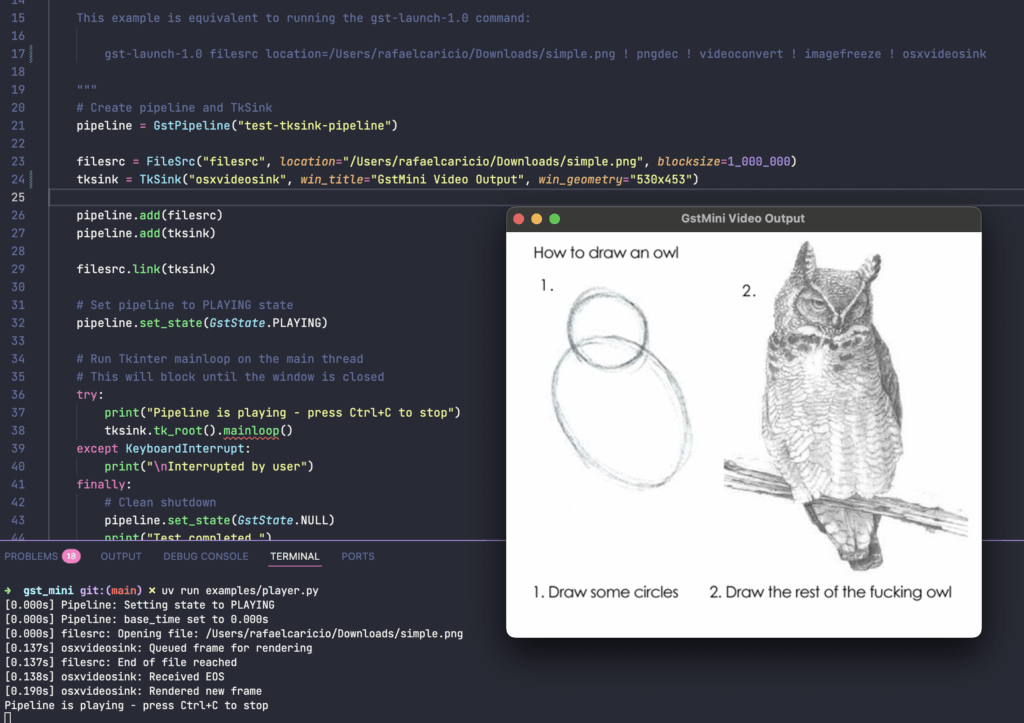

Can GstMini do multimedia? Why not?

While playing around with this project I decided to implement a small multimedia example. For that I implemented a TkSink for displaying frame bytes to a window canvas. I used Tcl/Tk GUI toolkit just because it was the lowest effort as it comes together with the Python installation (usually). Also a very simplified FileSrc element but that is essentially similar to the real filesrc element. You can look up the example here:

This example is almost a 1-1 usage of GStreamer, and you can even run this real GStreamer pipeline to replicate it:

gst-launch-1.0 filesrc location=$HOME/Downloads/simple.png ! pngdec ! videoconvert ! imagefreeze ! osxvideosinkOr using the actual GStreamer bindings for Python:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import gi

import sys

import signal

gi.require_version('Gst', '1.0')

gi.require_version('Gtk', '3.0')

from gi.repository import Gst, GLib, Gtk

def main():

Gst.init(None)

Gtk.init(None)

pipeline = Gst.Pipeline.new("test-pipeline")

filesrc = Gst.ElementFactory.make("filesrc")

pngdec = Gst.ElementFactory.make("pngdec")

videoconvert = Gst.ElementFactory.make("videoconvert")

imagefreeze = Gst.ElementFactory.make("imagefreeze")

gtksink = Gst.ElementFactory.make("autovideosink")

filesrc.set_property("location", "/media/simple.png")

pipeline.add(filesrc)

pipeline.add(pngdec)

pipeline.add(videoconvert)

pipeline.add(imagefreeze)

pipeline.add(gtksink)

filesrc.link(pngdec)

pngdec.link(videoconvert)

videoconvert.link(imagefreeze)

imagefreeze.link(gtksink)

# Create GLib MainLoop

loop = GLib.MainLoop()

# Handle bus messages

bus = pipeline.get_bus()

bus.add_signal_watch()

def on_message(bus, message):

t = message.type

if t == Gst.MessageType.EOS:

print("End of stream")

loop.quit()

elif t == Gst.MessageType.ERROR:

err, debug = message.parse_error()

print(f"ERROR: {err.message}")

if debug:

print(f"Debug info: {debug}")

loop.quit()

elif t == Gst.MessageType.STATE_CHANGED:

if message.src == pipeline:

old_state, new_state, pending_state = message.parse_state_changed()

print(f"Pipeline state changed from {old_state.value_nick} to {new_state.value_nick}")

return True

bus.connect("message", on_message)

# Handle SIGINT (Ctrl+C) gracefully

def signal_handler(sig, frame):

print("\nInterrupted by user")

loop.quit()

signal.signal(signal.SIGINT, signal_handler)

# Set pipeline to PLAYING state

ret = pipeline.set_state(Gst.State.PLAYING)

if ret == Gst.StateChangeReturn.FAILURE:

print("ERROR: Unable to set the pipeline to the playing state.")

sys.exit(1)

# Run the main loop

try:

print("Pipeline is playing - press Ctrl+C to stop")

loop.run()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\nInterrupted by user")

finally:

# Clean shutdown

pipeline.set_state(Gst.State.NULL)

print("Test completed.")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Wait! Is that GStreamer?

GStreamer is a project that has been built over 20 years by very experienced engineers dealing with multimedia processing. The simplification in gst_mini does not reflect in any way the amount of details and pitfals GStreamer prevents or takes care for you. A non-exhaustive list of features we did not cover in GstMini:

- No caps negotiation

- No events (except implicit segment)

- No queries

- No buffer pools or memory management

- No state change ordering

- No preroll mechanism

- Single clock (no clock providers/selection)

- No activation modes (push/pull)

- No scheduling/chain optimization

- No latency calculation

- etc

Many of the media services you use today may rely on GStreamer one way or another. Do not be fooled by the ugly GStreamer website! I hope this post was helpful to you and that it was inspiring for you to continue learning more about GStreamer.